Over the past few months, friends have reached out to ask about good anti-racist resources for their families. There are some valuable books and movies for adults, but for children, I have yet to find a book or show listed on a school DEI or anti-racist list that I’m a fan of. (Note that I’m sure they exist; I read a lot of children’s books, but I’m not a walking library!)

Race Cars: A Children’s Book about White Privilege by Jenny Devenny is one book that is included on a lot of local lists. I appreciate the goal of this book for preschool-younger elementary school children, but it unfortunately missed the mark for me.

Unfamiliar with the story? Read the summary or watch the video below.

Familiar with the story? Scroll down to the Unpacking the Book section.

There’s a white car and a black car who are best friends and love to race. Chase, the black car, is a better car racer than his best friend, white car Ace. So, the race organizing committee comprised of all white cars rigs the course and rules. It gets progressively tougher for Chase to win, and the last rule change ensures that Chase can’t race at all.

At the end of the book, Chase goes to support Ace in the race. Ace decides to try the route that Chase was forced to take after the race rules changed and realizes how much tougher this made the race. Then, Ace gets lost, and the race organizers are worried about him. They ask the fastest driver in town, Chase, to go find Ace. Chase agrees and ends up saving Ace! As a thank you, the race committee awards Chase first place.

Unpacking the Book

When reading a book, I look for the positives and then move to the critique. In Race Cars, I found the use of cars to frame Ms. Devenny’s point to be a poor choice. The paperback came out in 2016 – after Philando Castile was killed after a routine traffic stop with his girlfriend and four-year-old daughter in the backseat. This book had likely gone to press before this tragedy. But, studies related to the racial profiling of Black drivers existed long before 2016. Did the author, editor or publisher question whether this example would be off-putting or offensive to some readers?

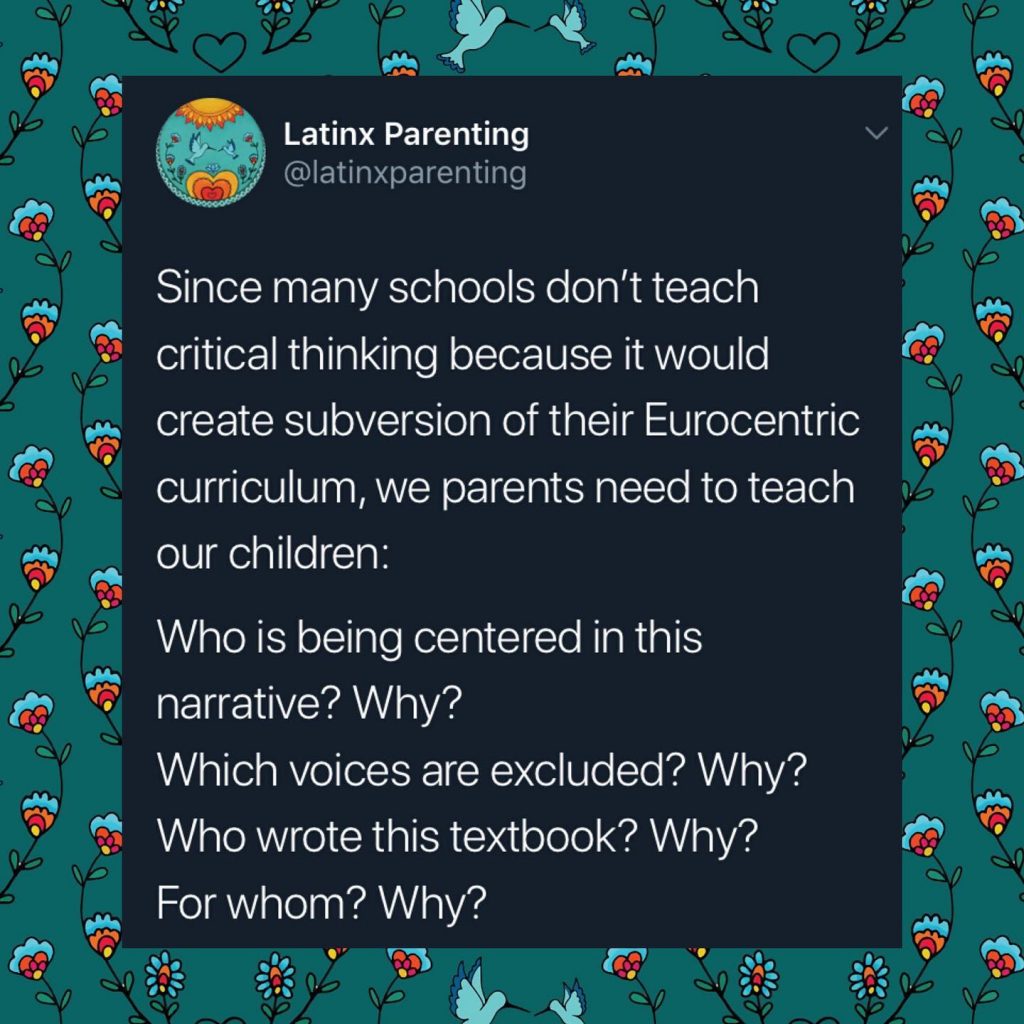

I also felt uncomfortable with Chase as the name for the black car, though I appreciate that rhyming words keep a younger audience engaged. Again, I would have chosen a different name, given the biased and false presumptions that Black drivers are more reckless or Black children aren’t as well behaved as white children. If I apply the critical thinking skills from my earlier post, I would guess the book’s target purchaser is a non-Black parent or educator. But, that doesn’t mean that the car example and name were the best choices.

The ending of the book also is problematic. The white race committee only reaches out to Chase to come back to the race because Ace, the white car, is in danger. The committee lets Chase win the race since Chase saves Ace – not because Chase is the fastest race car and not because all cars deserve the same access to entering and winning the race.

When Ace realizes how the race was tougher for Chase, Ace apologizes after Chase rescues him and then a hug solves everything. Even just adding a line in which Ace admits that he should have been a better friend to Chase and not entered the race by himself would have been something. I wish the book hadn’t been wrapped up with ease on a feel-good note.

The book was updated to include a brief Discussion Guide (shared at 15:46 in the above video from Neha Aunty’s Reading Room), and the last few questions ask kids to think of privileges that white people get and list them. Then, the guide asks whether the reader can find band-aids and dolls in their skin color.

Picture if this book is being read to a predominantly-white group of children. BIPOC children may feel further othered or marginalized if they raise their hands. Alternatively, this may force BIPOC children to feel as though they have to educate the white children in the room. This book might cause some children to think that there is a monolithic white or Black experience. It also could send the message to White children that recognizing privilege is a checklist item without having to do or think more about the topic.

Is this a worthwhile book to teach parents and educators about white privilege? I don’t envision most young white children will make connections on their own with this book without a lot of adult guidance from adults who have already unpacked their own identities and privileges. If children are able to connect that the race course represents our lives and access to opportunities, it can’t be assumed that parents and educators will find ways to help them relate the story to their own actions and larger structures of power.

Once privilege is recognized, what happens next? That’s what’s needed for action and change. I wish the book had offered solutions or resources beyond encouraging some brief acknowledgment that racial privilege exists.

As I’m reading and watching resources included on children’s anti-racist lists, I question whether the majority of predominantly white readers/viewers will know where to find reliable resources, how these resources should be critiqued and connected to their lives and larger power structures, and whether to share them with their children. My hope is that anti-racist resources are viewed as more than a checklist item or buzzphrase.

In my next post, I’ll write more about what adult resources I recommend regarding white privilege.

What anti-racist children’s books or shows do you like? Have any thoughts about this book or other resources regarding white privilege? Comment below or on my feeds!