During the Rodney King protests in 1992, I didn’t understand how the protest on my campus related to me. I think of numerous times in my teens and 20s when I did not speak up, made biased-filled assumptions or turned a situation that was not about me into a tear-filled response.

In my junior year in college, I began to read about white privilege. A lightbulb went off inside my head, but it seemed more like a checklist item.

Recognize privilege? ✅

Acknowledge privilege now and then? ✅

For far too long, I didn’t connect my privilege to the larger systems of power. Even when I looked critically at how the legal system, immigration law, and academia have been structured to perpetuate racial disparities, I didn’t delve into how my career roles and my whiteness made me complicit in these systems.

I know better now.

In Fall 2015, I taught a class using an article about racial health disparities that I had used successfully in previous years. A student comment led to some tension in the class. I learned that I needed to provide more of a background on structural racism, bias and privilege before asking students to examine health disparities in particular. I also invited two experienced speakers from the Black Student Alliance to class the following week. One student opened with, “We are all racists.” The room was silent…uncomfortably silent. But, what followed was one of the best discussions I’ve witnessed and led to several productive conversations outside of class.

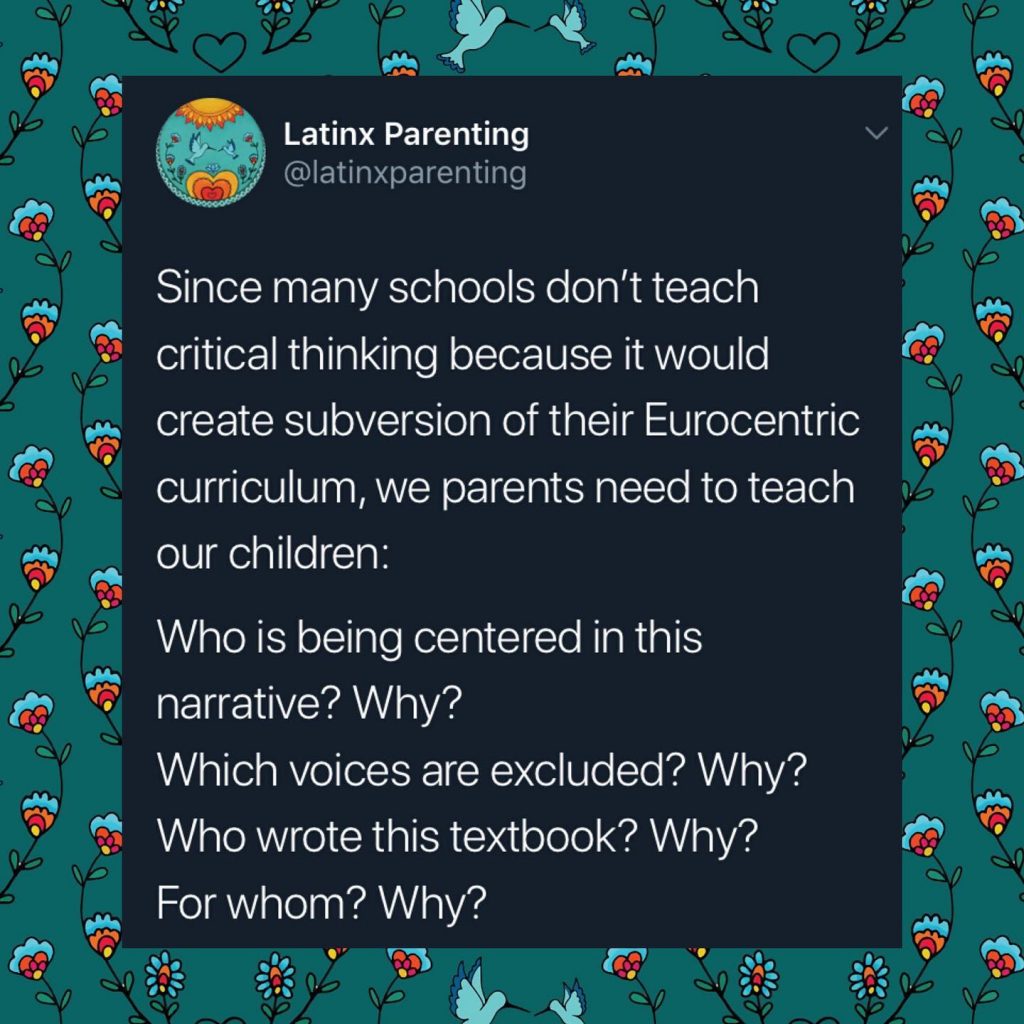

I’ve been speaking up about diversity and equity issues over the past several years, and I’m always willing to field a question from friends about whether a resource is problematic. Here’s the thing, though. Everything has some bias…all research…all writing…all people…even this site. I see critical thinking as allowing us to recognize and acknowledge biases so we can better analyze and interpret a source. I’ve also found that it helps me to educate myself more before I talk to Roya. I need time to process my thoughts and feelings before I help her navigate hers, while recognizing that there are many systems that benefit me that will marginalize her.

So where to start to learn about white privilege?

Here are some resources that I’ve found useful:

- What is white privilege? I appreciate how this Cory Collins piece for Teaching Tolerance references the 1988 Peggy McIntosh essay that coined the “white privilege” phrase. Collins also explains the importance distinction and relationship between white privilege, racism and power.

- In the US, children learn how Abe Lincoln freed the slaves. How do we as adults look beyond the history books? This piece by Dr. Mackubin T. Owens discusses how Black slaves freed themselves and what the Emancipation Proclamation accomplished. There are strong online lists of movies to learn about Black history, but it’s worth recognizing how these films have adapted true stories for Hollywood audiences. If you’re watching these films to learn about the past, I recommend an online search and reading a few critiques first. What’s factually accurate, and what isn’t? Why were these choices made? For an example of a good critique, check out this article about the controversy surrounding The Green Book.

In several classes, I’ve assigned a set group of resources that laid a good foundation for exploring privilege and biases and enhancing discussion:

- Harvard University’s Project Implicit bias test and Race IAT bias test — We all have biases. Let’s learn more about ours.

- “Hey White People: A Kinda Awkward Note to America by Ferguson Kids” — Watch through 2:10. This video pushes back on some popular rhetoric such as Love Sees No Color in an accessible way.

- “I Don’t Discuss Racism with White People” — I reference this quote by John Metta frequently: The entire discussion of race in America centers around the protection of White feelings. As a white person, I can feel and acknowledge my feelings. But, if I don’t move past my discomfort, then I’m centering myself – and my whiteness – in the conversation.

- How can those of us who do not identify as Black look for reliable information on our own? How do we know what we don’t know?

- If we read, watch and learn, what’s next? What does accountability look like?

- How is this connected to the systems of power we benefit from? What can we do to help change these systems?

- “What I Said When My White Friend Asked for My Black Opinion on White Privilege” by Lori Lakin Hutcherson — White individuals can ask Black friends for help, but it is not the obligation of any Black loved one to do so. In fact, asking individuals from a marginalized group to educate someone who benefits from racist structures of power can be further traumatizing or isolating, as explored in this journal article from Equity, Diversity and Inclusion.

- Park Avenue: Money, Power and The American Dream (PBS 2012) – “As of 2010, the 400 richest Americans controlled more wealth than the bottom 50 percent of the populace — 150 million people.” I’ve found this documentary useful to show the connection between power, government and economics in the US. Why is the American Dream an elusive myth? How do current institutions protect the wealthiest few at the expense of the majority?

- 13th Documentary (Netflix 2016) — “In this thought-provoking documentary, scholars, activists and politicians analyze the criminalization of African Americans and the U.S. prison boom.”

If these resources are new to you, then I recommend picking one at a time and not feeling rushed to get through them all at once.

What resources regarding white privilege have you found to be valuable? Comment below or message me!